An Impossible Rescue

An Impossible Rescue

In 1942, three Dutch leaders concocted a wild, outlandish scheme to rescue Jewish children from deportation, right out from under the oppressive watch of their occupiers. And the Nazis never discovered their secret.

Before the war, The Netherlands had been a neutral country, welcoming many German Jewish refugees across the border, but on May 10 1940, after promising not to attack, Hitler’s army swept furiously into Holland and overtook this beautiful land. The Dutch were stunned but consoled by promises that the persecution happening in Germany wouldn't occur in Holland. A special council—the Judenrat—was formed to meet the needs of Jewish residents, and they provided these Jewish citizens the best healthcare in the country at a camp called Westerbork. Even as new regulations were implemented in Holland, many of the 140,000 Dutch Jews believed they were safe because the Nazis granted thousands of exemptions to their growing list of rules.

Everything changed in July 1942 when the Nazis, assisted by the Judenrat, began rounding up Jewish citizens and cramming them into a gutted Amsterdam theater called Hollandsche Schouwburg. Residents waited there for days will little sustenance or fresh air before they were transported east.

Walter Süskind, the first of these three Dutch leaders, was a German Jewish salesman forced to oversee the registration and deportation of each man, woman, and child inside the theater. Across the street from the theater, separated by a tram line, were two brick-clad buildings that housed a daycare run by Henriëtte Pimentel, a matronly Jewish woman, and the Reformed Teachers’ Training College with a young principal named Johan van Hulst.

The children housed at the theater were quite loud, annoying the German soldiers, so Walter befriended the commanding officer and suggested they transfer these kids to the daycare. After the officer concurred, Henriëtte readily agreed to host them, and Johan and some of his teaching students volunteered to help. But they all wanted to do more than just offer these children food and shelter before deportation. They wanted to save their lives.

The German records were quite meticulous and regulated, but Walter, Henriëtte, and Johan devised a seemingly impossible plan. With permission from the parents, away from the oversight of the Nazi officers, Walter began eliminating the names of children from the registry lists. Once he erased them, these children—in the eyes of the Nazis—ceased to exist.

Still the Nazis kept an eye on the daycare center so Johan and Henriëtte concocted a number of ways to steal these unregistered children away. When the tram divided the daycare from the watchful eye of soldiers, for example, students would smuggle the kids out in laundry baskets, burlap bags, and milk cans. Sometimes they would take a dozen children on a walk and return with eleven. Or a baby tucked away in its carriage would be replaced with a doll.

More than six hundred children were rescued from theHollandsche Schouwburg. A miracle.

Each child was escorted to a safe home by a resistance worker, saving their life, but two of the three leaders who orchestrated their rescue died during the war.

In 1943 Henriëtte was killed at Auschwitz after accompanying her staff and the remaining children in her care.

Walter was exempted from deportation, but his wife and daughter were not. He chose to leave on a train with them and many think he was killed in 1945 by fellow inmates at Auschwitz who thought he, a former employee of the hated Judenrat, was a traitor.

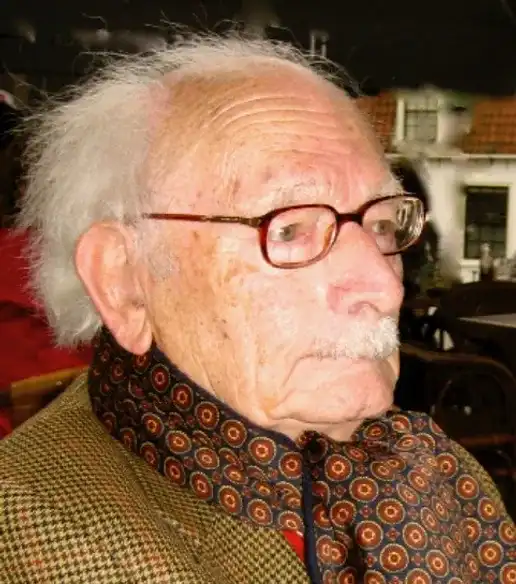

Johan van Hulst passed away last year at the age of 107. He knew that I was writing Memories of Glass, and it’s been a great honor for me to connect with those who love him.

Most of the Dutch who rescued children didn’t think they were heroic, and Dr. van Hulst was no exception. In fact, he once said: “I actually only think about what I have not been able to do. To those few thousand children that I could not have saved.” (Het Parool) The six hundred that he helped rescue, I suspect, think of him often. Memories of Glass was written to reflect both the corruption and heroism in Holland during World War II. It is a tribute, I hope, to those who risked everything to save a Dutch child.

All Rights Reserved © 2026 Melanie Dobson

All Rights Reserved © 2026 Melanie Dobson

Comments