What if I had lived in Germany during World War II?

After seven years of writing fiction set during the Second World War, this is the question that launched The Curator’s Daughter and took me straight into the heart of Nuremberg where Hitler once held Nazi Party rallies and later Allied Forces served justice in their military trials.

My journey to research this novel began in a college classroom outside Portland to learn the basics of working as an archaeologist. This was a guise, really. While Hanna Tillich, the heroine of my novel, was a German archaeologist, it had been a lifelong dream of mine to become one as well. During this class, I discovered that I’m much more passionate about crafting stories from the past than digging for artifacts, but in my manuscript, I began building a character who was passionate about preserving the legacy of her people.

After receiving my official certificate from the Oregon Archaeological Society, the research for The Curator’s Daughter took me on two remarkable journeys—one to the East Coast with my daughter Kiki and the other across the Atlantic to explore Germany.

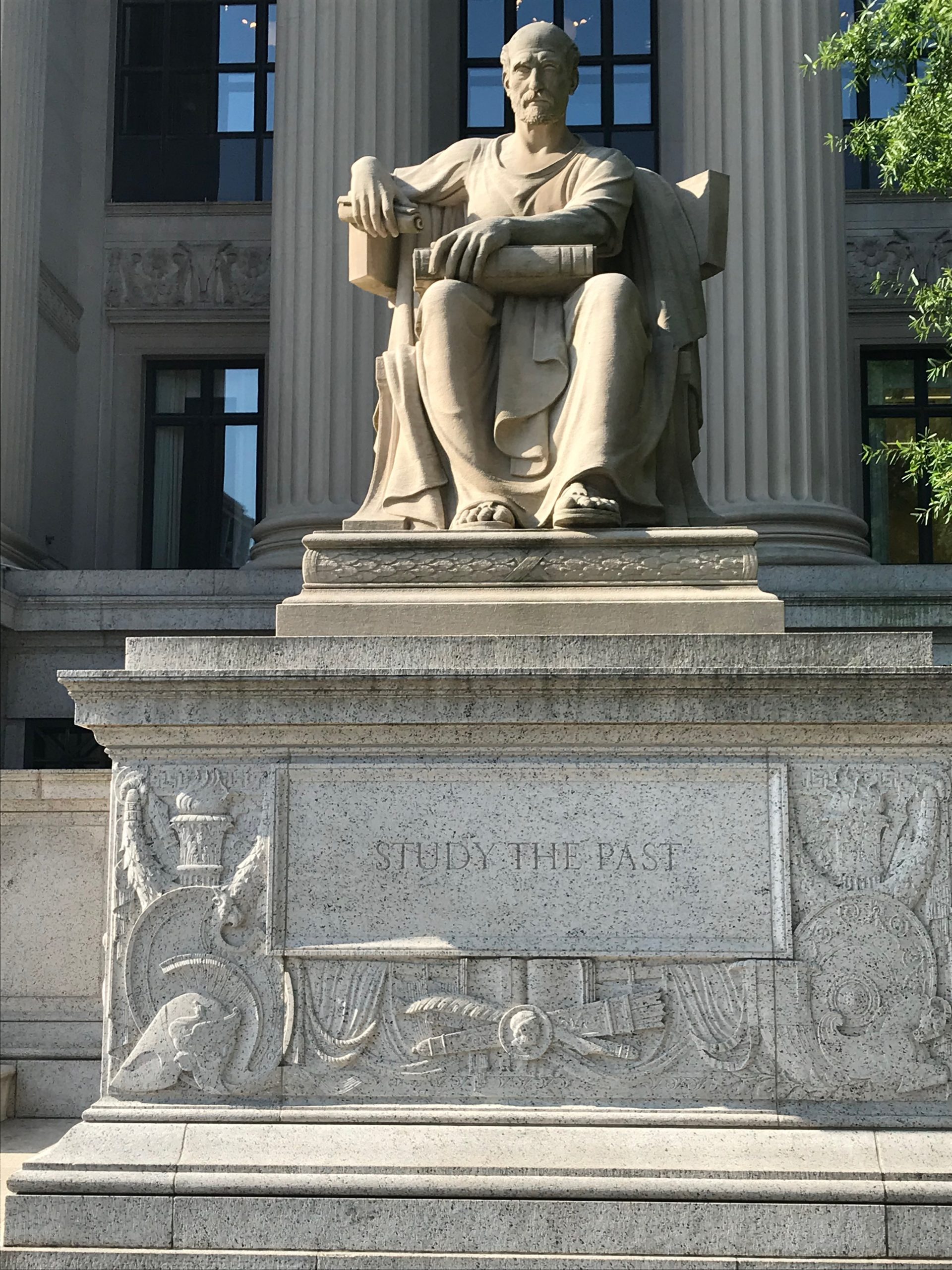

In Washington DC, I had the honor of reading through the Nuremberg Trial transcripts at the National Archives and interviewing both a research scholar and a Holocaust survivor named Ruth at the Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Keep telling the stories,” Ruth said. One of her greatest fears is that people will forget what happened in Germany just eighty years ago.

After a train and ferry ride north, Kiki and I explored the Victorian cottages and beaches on Martha’s Vineyard. Later I would visit Hayden Lake in Idaho, the setting for the Aryan Council in my book, but on this island I stepped into the world of my contemporary characters who were trying to escape their pasts.

Next I flew across the Atlantic to explore the medieval lanes in Nuremberg, the Nazi Party Rally Grounds, a (formerly) secret art bunker, Courtroom 600, several German toy museums, and the forested hills, sandstone quarry, and old zoo near where Hanna lived. Over a breakfast of fresh bread and quince jam, my friend Gabi shared her family’s war story, and we wondered together about the generation raised under Nazism.

One of the highlights of my trip was visiting the baroque Lutheran church in the German village of Pfungstadt, built in 1746. Several of my personal greats worshiped in the sanctuary including my double great-grandfather Peter Wacker who was baptized there in 1845 before immigrating to the United States.

Another baby was being christened the morning of my visit, and during the baptism, Pastor Dienst spoke about my ancestors’ legacy. About how the Christian heritage of Johann and Wilhelmine Wacker, through the life of their son, had passed down through the generations to me and my family. As I sat there steeped in the history, blessed by his words, I thought about identity, how we can embrace the good parts of our story and adopt new ones to replace the evil.

I would like to think if I’d lived in Germany in the 1930s and 40s that I would have stood up like so many did against the Nazi regime, but as I walked the cobbled lanes in Nuremberg, hiked the wooded paths above town, learned about the twisted propaganda that was delivered as truth, I realized it is impossible to say with certainty what I would have done. And it makes me even more grateful for those who stood up for what was good and right in that era.

The writing of this time-slip novel was a life-changing journey for me. As you read The Curator’s Daughter, I hope your life will be changed as well through both the past and present stories.

All Rights Reserved © 2026 Melanie Dobson

All Rights Reserved © 2026 Melanie Dobson