Twenty years ago I attempted to write my first novel by stitching together the threads from two plots—a past story about a woman who disappeared in Colorado’s mining country and a contemporary one about her great-granddaughter trying to find out what happened long ago.

I sent my manuscript to a dozen or so publishers and received back the same number of rejections. The general consensus—I needed to rip out the seams and rewrite, but I wasn’t sure how to sew the dual timelines back together again.

So I tucked away my idea along with a stack of drafts and began writing a contemporary novel about an unresolved conflict that happened decades earlier. After seven years of trying to publish fiction, my first novel came out in 2005, and I followed that story with several historical and contemporary novels that featured characters searching for answers from the past.

Then something magical happened.

In 2008, Tatiana de Rosnay debuted Sarah’s Key in the U.S. This novel wove together equally compelling past and present plotlines. Instead of having a character travel through time, the story spanned decades and the truth about the past ultimately transformed the contemporary protagonist’s life.

It was exactly what I wanted to write.

So I hunkered back down, studied the seams and structure of Tatiana’s brilliant book, and began writing another novel set in both the past and present—this one about a French woman during World War II who hid members of the resistance in tunnels under her family’s chateau. After I’d dreamed for years about publishing a past/present story, I was deeply honored when Chateau of Secrets won the Carol Award for historical fiction in 2015.

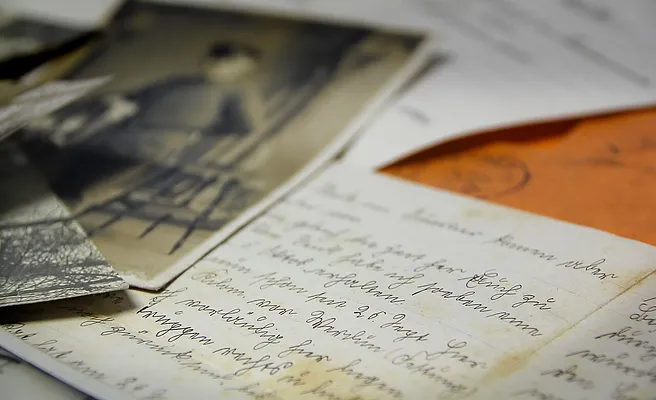

I wasn’t the only author who enjoyed this emerging format. In the past ten years, dozens have begun weaving together parallel past and present timelines, typically bridging the gap with a journal or heirloom that passes through generations and helps the contemporary characters uncover an old secret or redeem a past wrong.

According to a recent article in Publisher’s Weekly, this trend is continuing to grow. The big question, though, seems to be—what do we call this rapidly growing structure?

Publishers, authors, and readers call the multiple timeline format by multiple names. Time slip. Split time. Dual timeline. Twin strand. Time jump. Hybrid. A recent reviewer for My Brother’s Crown (Leslie Gould and Mindy Starns Clark) called their novel, “the melding of the two time periods.” In the Publisher’s Weekly story, Karen Watson of Tyndale House (my publisher) said, “There seems to be an ongoing interest in storytelling that bridges or twists traditional concepts of time and history. Rather than just straight linear historical fiction, we see a lot of novels that bridge two periods of time—what we call time-slip stories.”

I like time slip—this idea of melding together of two or more stories as the readers slip through time. And I like split time as well. The problem with dual timeline is that it narrows this format to two plotlines when some authors are branching out. Kristy Cambron’s novel Lost Castle is a tri-timeline story—the French Revolution, World War II, and present day. No matter what we call it, the important thing is that readers continue to be swept away by stories that transport them seamlessly across time. Fellow time-slip novelist Brandy Heineman and I launched timeslipfiction.com for readers who like inspirational fiction that slips between past and present. And if you're interested in writing time-slip fiction, Morgan Tarpley Smith and I have written A Split in Time: How to Write Dual Timeline, Split Time, and Time-Slip Fiction, a "workshop in a book" to help fellow novelists learn how to write in this emerging genre.

All Rights Reserved © 2026 Melanie Dobson

All Rights Reserved © 2026 Melanie Dobson

Comments